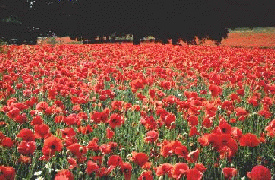

Yesterday was Remembrance Day. It might seem a little naff, but I wore my poppy. I like Remembrance Day and Anzac Day because they actually mean something. And more often than not, listening to the Last Post makes me teary. (If it's well-played - the bugler at my local Dawn Service this year should have had his bugle confiscated and been given a kazoo instead.)

Before you let me have it for being pro-war, I'm not. War is a horrible thing, but I can't deny that it interests me. Mainly, I'm interested in the effect it has on the people who see the meatgrinder up close: how they cope with going to war, seeing and doing terrible things and then just stopping it all and returning to ordinary life. In so many cases, they just don't cope.

I've done a few interviews with old diggers and they are always moving. I made a Rat of Tobruk cry once, and I ended up crying along with him. If you're in the mood, I'd like to tell you about some of the old diggers I've met. If you're not, that's fine. On the whole, though, they're humble men and they're far from being pro-war. They're your dad or your granddad or your great-granddad and they just did what they had to do at the time. And one day soon, they'll all be gone and we'll have lost something important.

The first war veteran I met was Gordon, and he was the one who affected me the most. He was a lovely old bloke who'd been a Rat of Tobruk and who'd fought at El Alamein. One of his mates called me to say he was about to turn 90 and he'd make a great story. I met them both down at the RSL one afternoon and we settled in for a drink. Gordon warned me not to call him "mister", even in the story. "I'm just Gordon," he said.

We had a bit of a chat about various things and he showed me his medals - and there were a lot of them. But when I got around to asking him whether he'd like to tell me about Tobruk, he said, "Oh, I don't talk about the war."

At the time, I was a miserable, green little hack and I thought, "That's something that could have been brought to my attention earlier!" but now that I've talked to more vets, I understand.

"In a soldier's life," Gordon said, "there are good times and there are bad, bad times." And those bad, bad times are just not for discussion with people who weren't there.

Gordon was happy to chat in the RSL, but he really wanted me to come back to his place and look at his old photos and memorabilia, so I went around a couple of days later. He and his wife lived in a little retirement village unit. He pulled out his old photo album and some framed pictures of himself as a young soldier. He showed me some black-and-whites taken while he was on R&R in Egypt and he looked like Lawrence of Arabia, sitting astride a camel with a larrikin grin on his face.

"Oh, I bet you broke some hearts in your day," I said, meaning it, and he laughed.

Seven months we were under seige in Tobruk, he said. The German Afrika Corps, commanded by the Desert Fox, Erwin Rommel, were on the other side of the barricades and things were looking grim. At one stage, the attackers tried to break down morale by flying overhead and dropping pamphlets that read, "You cannot escape! Surrender!" The Germans didn't realise just how happy the 14,000 Australians and 6,000 other soldiers inside were to have those pamphlets. They'd run out of toilet paper.

We chatted for a while and I looked through all of his souvenirs. "Can you pick me in that picture?" he'd ask. "What about this one?"

But as I left his little unit, Gordon grasped me by the elbow and fixed me with his faded blue eyes. "You just can't understand. Until you look into another man's eyes and see the fear of death in him, you just can't understand."

"And don't you make me out to be a hero," he called as I walked down the path with my eyes full of tears. "Because I'm not. I'm just an old soldier."

Next I met Bill. Bill served in Africa and on the Kokoda Track in World War II and he had won a French Croix de Guerre, but do you think he would say what it was for? "I don't know that I did anything different from anyone else," he said. "You only do what you're told and what you have to do."

The Croix de Guerre is one of France's highest military honours. Bill looked in his letterbox one day as he was on his way into town and found a little package. He put it in his pocket and hurried off the catch the train. Opening the box on the train, he found the medal - and nothing else.

"When I opened it, I knew what it was but I just thought, 'So I've got one then,'" he said. "Not many of them were given away, especially to Australians."

He was right, too. Australian general Sir John Monash got one in WWI and Australian spy Nancy Wake got one in WWII. Bill had been part of an Australian battalion that fought in Syria with the Free French forces. They were fighting against Vichy French allied with the Germans and their aim was to prevent Syria from becoming a Middle East base for Germany.

The local RSL tried to arrange a proper French Embassy presentation of the Croix de Guerre, but Bill's health went downhill and was too crook to go.

When Anzac Day rolled around, I spoke to John. John was a Rat of Tobruk who grew up proud of his miner dad, Jack, who had been at Gallipoli as one of the "Fighting 10th". John was a gentleman. He'd put on a freshly-ironed white shirt and a tie for his interview and photograph and he offered me a cup of tea.

"I thought the 10th must have been the most wonderful war unit of all," he said. When he enlisted in 1940, he was happy to find that he was to be a part of the new incarnation of his dad's old regiment, the 2/10th. He found himself thrown into the dying days of Tobruk and then sent to Palestine and from there to New Guinea to fight the Japanese.

"The noise of the battleground, the constant firing of artillery and mortars, the rifle fire and machine gun fire - it was neverending. If you hadn't grown up before then, you grew up very, very quickly," he said.

John was the Rat of Tobruk who I made cry and I still feel guilty.

"We're all scarred up in here," he said, tapping his forehead, "and it will never go away. I'm at a stage now where if I go to a service, I get terribly, terribly upset when the bugle plays the Last Post."

A few months later, I went down to talk to veterans of the "Forgotten War": Korea. I know M*A*S*H is still playing in re-run (and I still have a crush on Alan Alda as Hawkeye Pearce), but not many people remember the Australians who were part of that war. And some people still say it wasn't a war at all.

Betty was a nurse in Korea and as she left for her tour of duty, her WWII veteran father gave her a grim farewell. "If a bullet has your name on it, you will get it whatever you do," he told her. "Just do your duty." And Betty did do her duty, but when she came home in 1953, it was to a cold reception.

"They told us it was not a real war," she said. "They said it was just a 'police conflict'. For people to say that it was not a war...!"

Betty is a sturdy octagenarian with a bright smile, but even now you can see that she must have been a formidable nurse. She tells stories of using bedpans as toboggans to skate down snow-covered hills in the same breath as tales of surgery done during bombardments, just like those shown on M*A*S*H.

Ken was sitting with Betty as we chatted in the little Korea and South East Asian Forces Association hut. He was a "Nasho" - a National Serviceman - sent to war on a navy aircraft carrier when he was just 18.

"We were all afraid," he said. "We all have flashbacks." Not, of course, that they knew what was going on at the time. "I only know what was going on now because I read about it afterwards," he said. "At the time, you were only concerned with the man on your right and the man on your left."

In August last year, I met Len to mark the 60th anniversary of the end of WWII. Len could still fit into his old regimental jacket and still had his slouch hat, so he put them on for the photographer. When the war ended, he was a POW working in an Ohama coal mine. From his barracks, he could see into the Japanese guardroom and knew something was afoot when he saw the sergeant of the guard with tears running down his face.

"I mean, to see a Japanese officer crying," he said. "Then later on, came those four Japanese words that I shall never forget: 'No work. The war's over.'"

Len had been captured on Java in 1942 and had been a prisoner for just over three years when the war ended. Eighteen months of that time was spent with famed Australian army doctor Edward "Weary" Dunlop. "I still maintain that if it hadn't been for Weary Dunlop, we would not be here," he said. "Of course, there are only a few of us left now..."

Len's an old soldier who doesn't care for people who tell him he's obsessed because he can't forget the war. "I say, 'Have you had someone die? Do you forget them?' Of course you don't."

Then there was Jim. Jim stepped ashore in Hiroshima shortly after the surrender was signed.

"There was absolutely nothing," he said. "It was just flattened. I was looking around and imagining what Adelaide would look like if it were to be hit by an atomic bomb."

Jim was aboard the

HMAS Nizam, part of the fleet surrounding MacArthur's ship, the

USS Missouri, when the Japanese signed the surrender.

"We didn't know what they had done (when they dropped the atomic bomb)", he said. "A bomb was a bomb, we thought. We had no idea when we got there what it would be like." And what it was like was a few slabs of concrete bristling with reinforcing rod and surrounded by rubble.

But Jim still had a bottle of Hiroshima Bitter while he was there. "They were back making it two weeks after the bomb was dropped. It tasted OK - beer's beer, I guess. I'm just amazed we were never treated for radiation sickness."

Next there was Arthur. Arthur was a POW as well and he knew there was something afoot in August 1945 when the Japanese told them there would be no work for two days in a row. On the third day, their own officers told them the war was over.

Arthur was a member of the 2/3rd and had spent three-and-a-half years on what old soldiers call "the Line": the Burma Railway. They had all been made to wear wooden dog-tags to identify them during their captivity and when they were told the war was over, they all took the tags off and threw them in the air.

"The Japs saw the war was over and that was the end of it," he said. "They more or less disappeared and got out of our way. We were just delighted to get out of there alive."

Bert, on the other hand, was not a prisoner, but he still couldn't have a drink to celebrate the end of the war. "We were out among the orang-utangs, you see, in the jungle," he said. Instead of shouting for joy when they were told the war was over, Bert and his fellow soldiers walked quietly back to their barracks, sat down on their bunks and stared at each other. "Finally somebody said, 'I wonder how long until we go home?'"

For Bert, the real party didn't come until 50 years later, when the Adelaide veterans got together in the city for a commemorative march.

"A few tears dropped from my eyes that day," he said. "People were shouting and patting us on the back and children were running alongside and patting us. I ended up with streamers around my neck. That was a wonderful day."

Then there was Robert. Robert was a Vietnam vet and his was an

Apocalypse Now war. He spent his war aboard an army supply boat, travelling down densely-jungled rivers. The boat was called the

Clive Steele and it was one of what has become known as the Forgotten Fleet.

"I was one of the gun crew," Robert said. "It was only line of sight up the river and what you could see on the bank. We were just sitting ducks, really."

Robert spent just three months on the

Clive Steele before he was hospitalised in Vung Tau with glandular fever and pneumonia. By the time he was released, his boat had moved on without him and he had nothing but his pyjamas. "I felt a bit abandoned then," he said.

After a refit at the army supply store, he was stationed in Saigon, a city full of lost souls and refugees. He returned home in 1973 when Australia pulled out of Vietnam. "My personal view was that we should never have got involved in the internal politics of another nation," he said. "I think that was proved when we just walked away and left them."

Jean wasn't a soldier, or a nurse. She was a journalist and the Vietnam War was the story of her gernation, but Australian newspapers weren't sending female correspondents. She wanted to go, so she signed up as a Red Cross volunteer to try to help the Australian soldiers.

Jean knew she was in trouble when she saw a soldier's shattered body and felt nothing. "I thought he looked like a piece of meat in a butcher's shop window," she said. "I suddenly realised I had become totally devoid of emotion. I had grown immune to our daily reality, which was the appalling mutiliation and waste of young men's lives."

She ended up spending nearly a year "in country" and was one of just two women among 5000 soldiers. Always a little removed from the battles, she still saw the aftermath when the wounded were brought back to be patched up. Her job was to look after the welfare of the sick and the wounded, and she wrote letters for the soldiers, read to them and played cards with them to help pass the hours. She ended up with a nickname that was mildly embarrassing at the time, but that she now wears as a badge of honour: "Jean, Jean the Sex Machine". She wasn't one - it just rhymed.

She describes her time in Vietnam as the best year of her life. "I was so enriched by the experience, by seeing mankind at its finest," she said. "I have the highest regard for the Australian soldier - I've never seen such selflessness."

And then there was "Ike". Ike stood in the cemetery at Gona in PNG in 1943 and counted off the graves of friends who had died on the Kokoda Track. "I counted those crosses," he said. "There were 86 of my good mates there and there were another 15 missing presumed dead." And one of those crosses could just has easily have borne his name.

Ike had been second-in-command of his battalion, so it was only a chance decision of the brass that saw him left behind as the rest of his men marched away up the track. The day the first half of his battalion started the long march through the mountains, he was told he was leaving to take command of another unit. "I wasn't very happy about being separated from my mates, but what could I do?" he said.

The next time he saw his old unit, there were just 70 left alive.

And what about Jack? Jack was a code-breaker who carried cyanide pills in his pocket in case he was captured by the Japanese. He showed an aptitude for Morse code when he signed up in 1942, so the RAAF sent him to learn kana, the Japanese code. He wanted to be a pilot, but instead he became an Eavesdropper.

"If we got caught, we were to put the capsules in our mouths and crunch them and we would be dead," he said. "We were told to take our own lives so our secrets would not be revealed under torture."

The Allies broke the Japanese code early in WWII and men like Jack saved the lives of thousands of Australian and US soldiers, but killed thousands of Japanese. A single message that Jack intercepted resulted in the destruction of a 17-ship convoy carrying more than 10,000 Japanese troops.

"The only survivors were a few that managed to swim to shore," he said. "I sunk those ships and I had no feelings about it all at the time. I looked at it from the point of view that they went there to kill Americans."

And finally there's Ian. Ian spent 28 years in the Australian Army and served in what was then Malaya and later in Vietnam. As a part of the Australian Army Training Team, he spent most of his nine months in Vietnam out in the field with South Vietnamese army units.

Ian doesn't like to talk about the war either. "Battle's another part of your life," he said. "Why do you need to talk about it?" When he goes into his local RSL, it's not to talk war but to remember old friends.

"I haven't heard anyone tell a warrie in years," he said. "Why do you need to talk about it? I know pretty much what that bloke did and he knows what I did."

I'm not suggesting that war is right and obviously I'm not saying that the current war in Iraq is right, because it's not. I'm also not suggesting that we should lionese everyone who went to war and call them heroes just because they were in uniform.

All I'm saying is that we shouldn't forget.

Labels: remembrance day, war